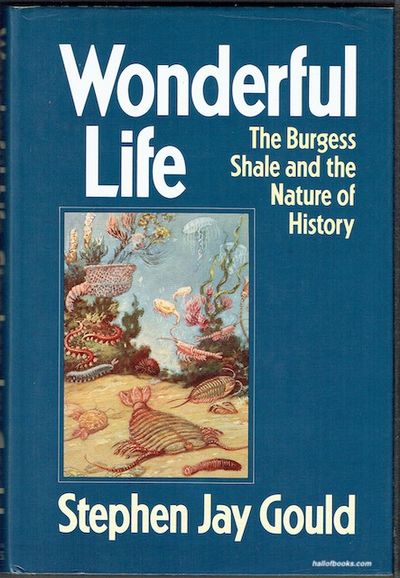

In his book Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History, paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould enthralls the reader with his captivating theory of the deep past. His central thesis is that evolution is not a linear progression of less-to-more advanced forms, as is popularly thought. Instead, Gould argues that evolution is a series of decimations, followed by diversification of the few lucky survivors. He backs this up through a narrative of the ancient fossil bed known as the Burgess Shale.

Although many of Gould’s reconstructions are outdated, having been published in 1989, his writing is still very much relevant to this day, as the very same popular misconceptions about evolution that he debunks are still widespread in modern times.

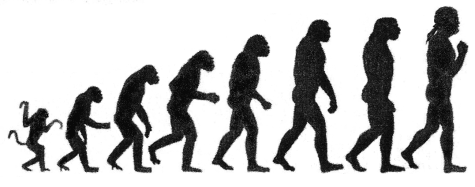

Gould begins his book by talking about the popular models of evolution.The first is the March of Progress, which is the one that you are probably most familiar with. This model presents the procession of apes, each standing more upright than the last, ending in humanity.

The second model is one you may have seen in your biology textbooks: the cone of increasing diversity. This model shows life starting out from a single line and splitting more and more, getting even wider until, at last, its maximal breadth is achieved at the very top of the tree, representing, of course, the fauna of today.

Both of these ideas imply a progress of a sort. The first, and less accurate, is shown as a direct line, a ladder where each rung is more advanced than the last. The second model, although more accurate, still displays improvement—simple generic forms predictably give way to a vast crown of complicated and diverse life.

Both models are comforting, states Gould, because they show a preordained sequence, simple to complex, all leading up to our ourselves, humanity, chosen of divinity, the end goal of evolution.

Gould, however, disputes this. Evolution, he says, is neither a ladder or a tree. If anything, it’s a pyramid, with the greatest diversity at the bottom, wherein lies a soup of possibilities.

Time, however, chooses winners. All but a few of the initial possibilities go extinct, and evolution generates variations on the few survivors. These fortunate beings follow the same trajectory, of a bottom layer of endless possibility whittled down to a few survivors, who split into variations on their own form.

An important part of this is the semi-random selection of those few victors. Those who live on are not necessarily superior to those who didn’t. They simply happened to luck out, and they simply happened to possess “a feature evolved long ago for a different use [which] has fortuitously permitted survival during a sudden and unpredictable change in rules,” according to Gould.

Most of the rest of the book is devoted to the Burgess Shale, a fossil bed found in British Columbia, which provides the evidence for Gould’s bold assertion of this theory of decimation. He gives a fascinating account of the discovery and interpretation of the fossils buried at this site, specifically, by one Charles Walcott, an administrator of the Smithsonian Institute.

Gould coined the term “Walcott’s shoehorn” to describe how Walcott misinterpreted these fossils to fit his own biases towards a linear evolutionary theory. Walcott mistakenly classified them as primitive members of known groups, even when it made no sense for him to do so.

Unfortunately, many of the reconstructions that Gould uses as the correct, modern ones are also severely outdated by now. His Hallucigenia, for instance, is turned upside-down. However, his point, about the incredible diversity and strangeness of the Cambrian biota of the Burgess Shale being missed by Walcott, is still valid.

At the end of the book, Gould applies his theory of contingency to natural history, and he speculates on possible alternate paths that life could have taken. For instance, eukaryotic life—that is, life bearing a mitochondrion, including protists, fungi, plants, and even animals like us—could have simply never evolved at all.

For the vast majority of the history of earth, only bacteria existed, and it very well could have continued on like that forever, or at least until the gradual expansion of the sun renders the earth uninhabitable. If the mitochondria had never evolved, all the complex multicellular life that we now have today, from oyster mushroom to pine tree to human, would simply not exist.

Gould also raises a host of other possibilities as well, such as terrestrial vertebrates never evolving, or priapulids being as successful as annelids are. Each one of these outcomes would have resulted in a world quite alien to the one we know today.

Although the book is by now decades old, and the author has been dead since 2002, Wonderful Life is still very much worth reading. The paperbacks can be purchased from Amazon for only $13. This is a purchase well worth your money, so I suggest you check it out!