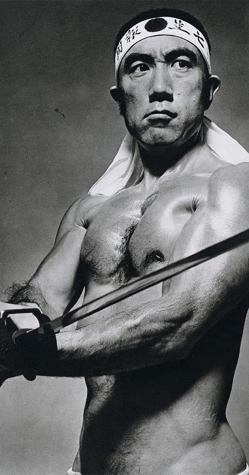

Yukio Mishima was a main character in all senses of the word. He was, to say the least, crazy. He was a Japanese bodybuilder, actor, model, closeted homosexual, hyper-masculine, militia leader, novelist, poet, nationalist, launcher of a failed coup, a post-modern samurai. But above all, Mishima was a beautiful author.

Yukio Mishima was a main character in all senses of the word. He was, to say the least, crazy. He was a Japanese bodybuilder, actor, model, closeted homosexual, hyper-masculine, militia leader, novelist, poet, nationalist, launcher of a failed coup, a post-modern samurai. But above all, Mishima was a beautiful author.

I read John Nathan’s translation of The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea, a philosophical bildungsroman on nationalism and glory, and there a few other books that I could recommend more.

The first thing that pulled me in about this book, and the most consistent and evident, is Mashimi’s beauty in writing. I am not sure if this is to the credit of Nathan, of Mihima, or of the Japanese language, but Nathan’s reluctance to change the syntax of the original Japanese work and language, which paints pictures like an image, is a work of astonishing creativity. The way Mishima uses syntax, so experimentally with clauses used unlike anything written in English, sets him apart from anyone else.

Often when I read translated works, they fail to capture the magic of the author. With some popular writers, each translation sounds like a different book. With Dostoevsky, each translation is less a translation and rather a rendition. This may be the case with this book, but Mishima’s style is so bright and unique that it shows and amazes.

The pacing and the format of the story is something you would expect from postmodern fiction. It plays without a plot yet with a reason for the story, with characters motivated and changing throughout. The story follows a sailor, with big aspirations from his youth, who finds love with a single mother who owns a Western luxury goods store and has a son that is in a rebellious gang of child philosophers.

The novel is a coming-of-age story from the perspective of narcissistic teenagers apart from the conventional morality, obsessed with the idea of being the Ubermensch of restoring Japan’s former glory; the sailor, a modern samurai in a sort, becomes their ideal. But as the love between the mother and the sailor grows, and as he becomes more “domesticated”, the gang plots to assassinate him as a way of cleansing the world into their idea of a perfect society.

It is not hard to find the metaphors for glory and Japanese Bushido in the form of nationalism, as after Mishima’s own coup (motivated that Japan’s constitution was an admittance of defeat) he killed himself, not unlike the way that it is presented in the novel. He uses philosophy, deeply rooted in brilliantly furnished and colored fiction, and it is sometimes hard to detach the author’s violent twists of Nietzsche’s ideas from what I can best describe as the lovechild of Mussolini and Nabokov.

You must be wary as a reader to stand your intellectual ground, and to read into this piece studiously, but you should not take this as only a story or as a philosophical truth, but rather as the eloquent writings of a would-be fascist.

That said, I cannot sing enough praises for this book. It does have an interesting take on European philosophy that you cannot find anywhere else but in the traditions of Taisho and Showa era Japanese literature. It does have a unique, exuberant style. It does use story in an experimental yet interesting way, and when I really stretch my brain for anything I can critique about it, I cannot find much to say.

My only critique of the novel may be that the mother is not as fluently developed as much as the other characters are, and so when the climax happens, she is pushed away like a device for the theme to bleed through. However, I really cannot complain much about that, because you cannot find a philosophical novel that does not fall for that trap.

You need to read this book! If you have any biases toward the author that I have planted in your brain from this review, try to leave them behind and enjoy it for what it is: a postmodern classic that anyone with an inkling of respect for literature will be astonished by.

Needless to say, I loved The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea. You will, too.