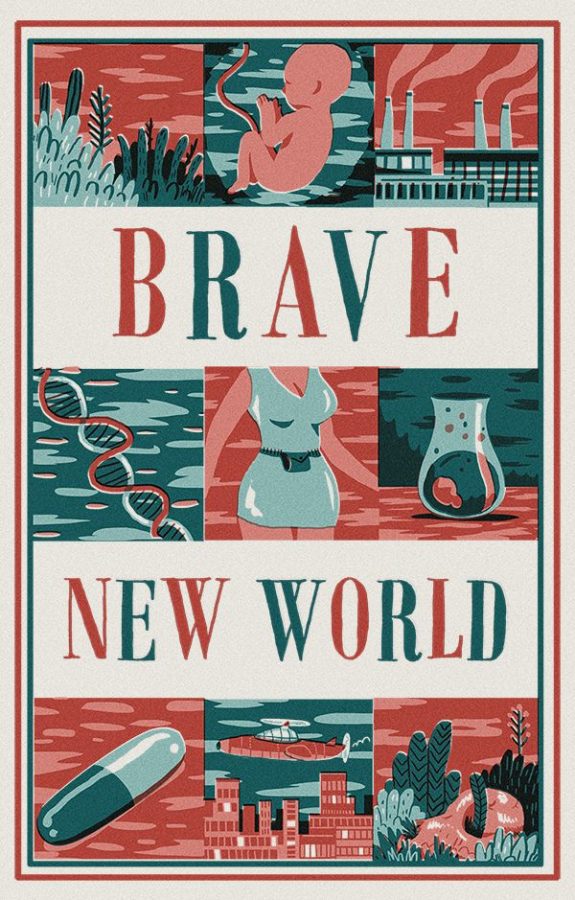

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley has been adapted to Peacock (NBC’s streaming service), and to tickle our journalism teacher, who has been pushing us to do a “How Does It Hold Up?” series all year, I have decided to start the series with a review of the novel.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley has been adapted to Peacock (NBC’s streaming service), and to tickle our journalism teacher, who has been pushing us to do a “How Does It Hold Up?” series all year, I have decided to start the series with a review of the novel.

Published in 1932, Brave New World was released to generally negative reviews, with one reader, a literary critic of the British magazine New Statesman and Nation, saying, “Mr. Huxley does not really care for the story–the idea alone excites him.” Among many others, M. C. Dawson of Books, called it a “lugubrious and heavy handed piece of propaganda.” (Leave it to a literary critic to use the word “lugubrious”.)

But the novel has fared better as the book has grown older, with teachers even forcing it upon kids. Some people attribute its late success to its prophetic nature, or the Zamyatin-like themes that would later influence George Orwell, another author pushed on unwilling high school students.

But in its pages is a sci-fi work, and I think we must judge it accordingly. It should be evaluated not as libertarian propaganda, not as a story with the idea to entertain, but like Charles Beaumont and many sci-fi writers do, it should be viewed as a story and an idea with a theme. And in that respect, it does its job well.

To Kill a Mockingbird, widely considered a great book, is a cluttered mess of short stories for the first half, but we see it as a book presenting a theme and judge it accordingly, agreeing that it is a good book. When you read a dictionary, you cannot expect complex characters with deep conflicts and a well-constructed story. You cannot say the dictionary is poorly written because it has no narrative. If the goal was to provide a narrative, and there is no narrative, then it is fair to judge it that way.

But a dictionary’s job is to teach, and I think the same can be said of Brave New World. It is an essay with a story, so I will review it by understanding what it was trying to achieve and judging it accordingly.

As I understand it, the book was trying to criticize the growing idea in industrialized, totalitarian England, where commercialism and a predestination-like classism ruled with hedonistic, utilitarian power and belief. And at this, the novel succeeds in showing how all these forces of modern England dissolve into this dystopia and tangle with each other into the setting.

Commercialism, shown very often throughout the book in the destruction of old, unmarketable things, works with the late-stage capitalist world of very powerful corporations. The totalitarian government works with the predestined classism enabled by the hedonistic soma, leading to humanity getting stuck without progressing to the next stage, all of which are enabled by utilitarian thought.

Huxley weaves these ideas together masterfully, so that a sophomore like me can figure them out, and sound pseudo-smart long enough for people to walk away from me mid-conversation at social gatherings. Although what you take away from the book relies on the diligence of the reader, it is not hidden to the philosophically-inclined. It is meant to reach and educate a vast audience, and that it does well.

But it is an essay with a story, after all, and the story contributes to the quality of it. And I must agree with the critics, because the story is shallow, more of a description of a setting than a narrative. The characters don’t undergo any sort of change or many dramatic shifts. No events really occur, and the beats of the story can be described in one or two sentences.

The story does not ask you to become attached to the characters or to be shocked by this twist or that twist. It is using characters as examples of the human effects of the world they live in, a showcase of the setting.

But, at the very least, the story is not scattershot or incoherent. It is only simple and an extension of the theme, a checklist of the theme and its repercussions. If the story was overly complicated and got in the way of the essay, then the story would lose points. But it doesn’t and these two aspects work well together (albeit sacrificing a depth, a risk unrisked, one worth taking).

This review would usually be longer to discuss the other aspects of the book, but there aren’t many for this one, and so I will end it here. Although the theme and setting of Brave New World are masterfully thought-out and projected well in the book, that is all it has, and Huxley does the bare minimum needed to create a book of an essay.