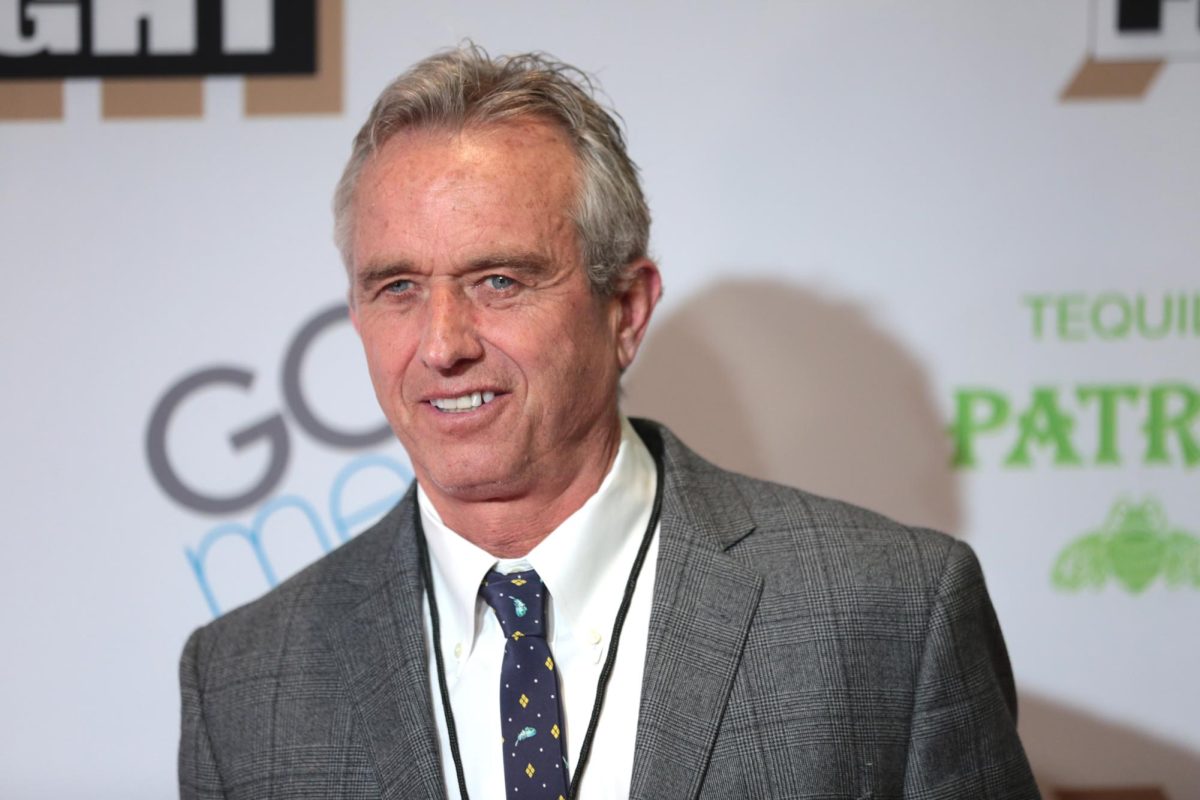

If you’ve been paying any attention at all to the news, you’ve probably heard the recent story of third-party presidential candidate Robert Francis Kennedy Junior and the brain-eating parasitic worm that was found dead inside his brain.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr, of the same Kennedy family that produced one president and a host of congressmen and ambassadors, has been in and out of the news this election cycle. Compared to usual third-party candidates, he’s doing astonishingly well. There’s even a chance he might get on enough ballots to qualify for the Presidential Debate in June, which would be the first time a third-party candidate has done so since 1992. And although he almost certainly won’t win, Kennedy might still affect the outcome of the election— primarily as a spoiler candidate, either for Biden (due to his family affiliations and environmentalism) or Trump (due to his anti-vaccine activism).

Regardless of whether or not he ends up having any actual effect on electoral outcomes, Kennedy has still been in the public eye long enough that people have started digging. And so we have learned that, during a 2012 court deposition where he was in the process of divorcing his second wife, Kennedy stated that he’d been experiencing memory loss and mental fatigue, caused by a combination of mercury poisoning and the now-famous brain-eating worm.

We often think of our minds as fundamentally separate from our bodies, some sort of essence totally alien to our flesh, with the wet matter of our earthly forms merely a puppet of some greater soul. But of course, as Kennedy’s case demonstrates, this is not true.

We do not live in our flesh, we are our flesh. The mind is sourced from the meat, an emergent property of the complex living system that we call our body. And so ailments of our body, like mercury poisoning and parasitic infection, can produce effects in our minds, like the cognitive issues Kennedy suffered.

It’s not even just the brain, either. Our entire bodily system contributes to the consciousness we currently experience. Even the microbes which live inside us–and outnumber our own cells–can influence our minds, and mental health.

Given that gut bacteria have effects on our brains, it’s no surprise that parasites can as well. There are many examples of these in the animal kingdom, such as the ant-controlling Ophiocordyceps made famous by The Last of Us, or the “horsehair worms” that make grasshoppers drown themselves,

Luckily, both of these examples are parasites that target insects, not vertebrates and certainly not humans. But even parasites that don’t intend to target humans can still have a negative effect on them. The horsehair worm, for instance, which on a few occasions people have accidentally ingested, can apparently cause orbital tumors in human facial tissue.

Now, we don’t know the exact species of parasite that burrowed into Mr. Kennedy’s brain. But Francisca Mutapi, a professor of medicine interviewed by NPR, speculated that the specific condition Mr. Kennedy was suffering from was neurocysticercosis, a disease caused by tapeworm larvae. Note that this is specifically tapeworm larvae, not tapeworm adults. To understand why this matters, you must first understand the tapeworm lifecycle.

Tapeworms are fairly simple animals, but their habits are more complicated. Almost all tapeworms need at least two hosts to reach maturity.

There are two kinds of hosts. There’s the “definitive” host, which is to say the final one, the animal in whose intestines the worm will develop to full adulthood and start laying eggs.

And then there’s the “intermediate” host, which a tapeworm will parasitize before reaching adulthood. It will then burrow into the flesh of this host, forming a cyst. Then when the flesh of its intermediate host is consumed by the definitive one, it will transform into an adult.

Humans are the intended definitive host of a few species of tapeworm, including the pork tapeworm, which researchers believe Kennedy may have been infected by. Those same species generally use livestock, such as cattle or pigs, as their intermediate hosts. Their eggs will hatch into the larva, infecting livestock through contaminated water. The cysts will hatch into adults, which will be ingested by humans through meat consumption (hence the “pork” in the pork tapeworm).

When all goes right, a human serves as the final host, with an adult worm growing inside their intestines. This is called Taeniasis, which is a comparatively minor, almost harmless condition.

But when this goes wrong, as happened to Kennedy, the human may be infected, not by the adult stage, but by the larval one. The worm burrows around and forms a cyst in the tissue of its host, as is normal, but unlike pigs, human flesh is only rarely consumed by other humans.

As such, this is an accident that is bad for both the worm and the host, as the worm will never reach maturity and the human will suffer the horrible effects of the cysts. This is especially harmful if the worms happen to get into the nervous system before encysting, in which case they can cause a host of neurological problems. For instance, they are the main cause of epilepsy in the developing world.

If the worm in Kennedy’s brain really is a tapeworm cyst, then the infection was an accident, a fail state. The worm’s odds of making it to maturity were as low as Kennedy’s own chance of becoming president.

Truly, it’s a tragic tale. And yet perhaps I feel more for the plight of the worm than for a man who says that Israel is a “moral nation” (even as it bucks international law while on trial for genocide) and brags of his relationships with Jeffrey Epstein, Harvey Weinstein, OJ Simpson, and Bill Cosby. Unlike the worm, though, I somehow doubt that Kennedy’s odds of success would be much improved by the widespread adoption of cannibalism.