If you’ve been keeping up with movies recently, you may have watched a certain trailer for Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, where little girls gather around the film’s star, and they are quickly driven to the destruction of their other toys as they are taken in by the magic of Barbie.

If you’ve been keeping up with movies recently, you may have watched a certain trailer for Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, where little girls gather around the film’s star, and they are quickly driven to the destruction of their other toys as they are taken in by the magic of Barbie.

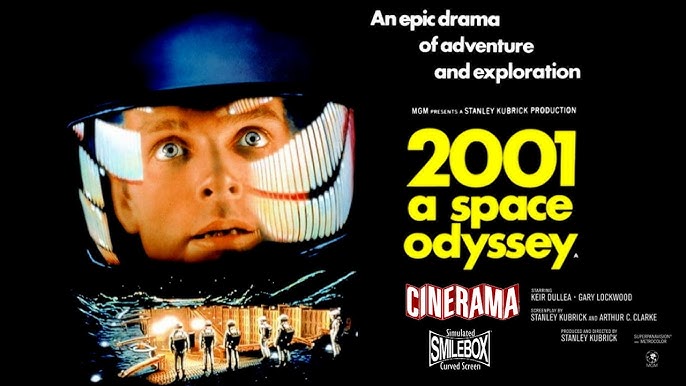

However,you may not know what this trailer is referencing: the classic 1968 science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey. But even if you’re only vaguely familiar with the contents of that movie (and indeed, it’d be hard not to be, as the movie serves as somewhat of a pop-culture touchstone), you probably haven’t actually seen it. Indeed, a recent, in-person (and not very scientific) poll of Mr. Livingston’s 4th Period Journalism class revealed that the vast majority of students had never seen the film. And many of them hadn’t even heard of it.

This, of course, is a mistake that can be easily rectified. And a mistake it is.

2001: A Space Odyssey, even though confusing at times, is a true masterpiece of cinema, holding up even today, over half a century since it was first released.

Perhaps the most immediately notable aspect of the film is its special effects. Far before the age of modern CGI, the relatively primitive technology of the time lends 2001 a certain charm not found in modern cinema. There’s a certain solidity to everything you see, and at the same time, a sort of weightlessness, which really contributes to the otherworldly nature of the movie.

That is, the practical effects found in the film–like building an actual giant rotating room for the interior scenes of the Discovery One–have really held up well. Their antiquity is more charming than ugly.

The pacing, and the overall feel of the film, is also very noticeable. The movie consists of large stretches of somewhat serene space-age imagery, interspersed with dramatic scenes, which nevertheless still possess a great measure of restraint.

The pacing, and the overall feel of the film, is also very noticeable. The movie consists of large stretches of somewhat serene space-age imagery, interspersed with dramatic scenes, which nevertheless still possess a great measure of restraint.

2001 is, however, far from boring, as the slow pace serves to fully display the wonder of the fantastic future depicted on screen. This allows the viewer to marvel at space stations as built-out as airports, at exploration-trucks flying above the lunar surface, and at colossal sleeper-ships, with centrifugal gravity advancing relentlessly through the blackness of space.

Of course, the primal sequence at the film’s beginning, with apes warring across the savannah, who are granted intelligence by the appearance of an alien monolith, is not at all restrained. But even as the proto-men scream, howl and rage on screen, the film itself remains still.

The characters of the film are, as previously implied, very much subdued. Really the most emotional character in the entire film is the HAL-9000, the actual lifeless machine. It is clear from his actions that, despite his stilted voice, he is driven more by human emotion than any of the actual homo sapiens sapiens on the crew.

Dave, the ship’s commander, for instance, even as driven into a practically incandescent rage, remains totally silent, restrained, and professional, while HAL begs and pleads for mercy, clearly panicking despite his unwavering monotone. Certainly HAL’s eventual fate ranks high among the most dramatic, most tragic scenes of the film.

2001: A Space Odyssey is very much a cultural landmark, and its prominence in our cinematic lexicon is well-deserved. If you can spare the time, give it a try.